For decades, Moore’s Law, the observation that transistor counts on chips tended to double every two years, served as the driving force of the semiconductor industry. But as physical scaling hit formidable walls, engineers turned to less visible innovations to sustain performance. One of the most understated players in this saga is the standard cell library, a modular design system that helped maintain the illusion of continued progress. Midway through this unfolding shift, Erik Hosler, a strategic advisor who connects semiconductor development to consumer outcomes, reminded the industry that perception matters just as much as physics.

As engineers quietly optimized at the design level, most consumers remained unaware of the profound changes under the hood. While process nodes stagnated, chips kept getting smaller, faster, and more efficient, thanks not to radical breakthroughs but to clever refinement. This silent success story highlights the importance of system-level thinking and architectural finesse.

Cracks in the Scaling Story

The end of transistor scaling was expected to be a clear-cut moment, a line where we’d exhausted physical limits and the silicon era would slow dramatically. But the reality turned out to be far more nuanced. Around the 90-nanometer node, process scaling began to encounter barriers, both technical and economic. Issues like leakage currents, power density, and rising fabrication costs made continued scaling challenging.

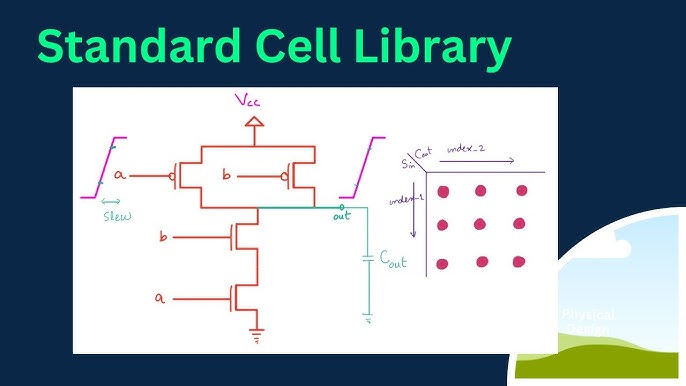

Yet despite these roadblocks, chips kept advancing in performance and efficiency. Consumers enjoyed sleeker phones, smarter applications, and improved battery life. So, how was this possible? The answer lies, in part, with standard cell libraries. These are pre-designed collections of logic gates, such as NANDs, NORs, and flip-flops, that engineers use to assemble digital circuits. Improvements in these libraries allowed designers to get more from existing technology nodes. These advances weren’t flashy but rather cumulative: smarter placement, tighter routing, denser layouts, and better transistor modeling. Together, they enabled each new chip generation to appear improved, even when lithographic scaling had slowed.

The Great Disguise

When Rob Atkin of ARM noted that Moore’s Law had already been saved by standard cell and SRAM designers, he was pointing to a truth well-known within the industry. While lithographic advancements had decelerated, design ingenuity quietly filled the gap.

Through careful engineering of standard cell blocks, designers improved performance without relying solely on new fabrication techniques. They enhanced what was already available, refining every corner of logic design to keep delivering better results.

This approach made the stagnation invisible to the average consumer. Product releases stayed on track, and performance gains were maintained. Moore’s Law, though technically off course, seemed alive and well to the outside world.

Perception vs. Physicality

This contrast between technical stagnation and perceived advancement underscores the brilliance of standard cell library development. These design-level changes allowed engineers to reshape the computing experience without requiring changes to the underlying physics.

Erik Hosler shares, “This is because consumers don’t care what the feature size is inside a chip.” This insight captures the crux of the modern tech landscape. Users aren’t focused on transistor size or process nodes. What they care about is whether their devices run faster, last longer, and offer better capabilities. If a smartphone unlocks instantly, streams without buffering, and manages AI features seamlessly, then the manufacturing details become irrelevant.

This consumer-first perspective has permitted engineers to innovate in other areas, prioritizing system performance and software integration over traditional scaling. And standard cell libraries have been essential to that transition.

Optimization as Innovation

In today’s semiconductor world, scaling no longer refers only to lithography. It encompasses optimization across all layers of the design stack. Standard cell libraries embody this approach. Instead of introducing entirely new materials or machinery, engineers maximize the efficiency of what they already have.

This mindset echoes trends across the industry. Domain-specific architectures like Google’s Tensor Processing Units and Apple’s Neural Engines are gaining traction. Chiplets and heterogeneous integration are being used to combine specialized functions. Advanced packaging is being developed to reduce signal delay and improve thermal control.

In each of these innovations, the foundation often begins with the libraries. A well-crafted standard cell library makes all other layers more efficient and easier to manage. It offers a reliable starting point for increasingly complex design challenges.

Beyond Lithography

The SPIE Advanced Lithography symposium highlighted a key truth: Moore’s Law will not be saved by any one solution. It will require a collective effort involving materials science, AI, metrology, and architectural improvements.

Standard cell libraries are an essential part of this broader strategy. They may not grab the spotlight like Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) lithography or quantum computing, but their impact is undeniable. These modular components allow engineers to continue delivering better performance from mature nodes, often delaying the need for costly process upgrades.

This strategy also contributes to sustainability. Reusing and optimizing standard components shortens development cycles, reduces errors, and increases design reliability. These benefits not only save costs but also minimize the environmental footprint of the chip development process.

From Law to Philosophy

In the end, standard cell libraries tell us something profound about the development of Moore’s Law. Once a metric tied to physical scaling, it is now a broader philosophy, a commitment to continuous progress, even when traditional paths are blocked.

The real value lies not in counting transistors but in rethinking what it means to move forward. Can we do more with less? Can we innovate through optimization, not just invention? Can we continue to surprise and delight users even when silicon physics becomes less cooperative?

The quiet contributions of standard cell designers answer these questions affirmatively. Their work proves that innovation doesn’t always have to be dramatic. Sometimes, the most important advances are the ones we never see.

A Quiet Triumph

Standard cell libraries don’t command headlines, but they are the unsung workhorses of the semiconductor industry. Without them, the illusion of uninterrupted progress might have been cracked years ago.

In a world where Moore’s Law is being debated more than followed, it is fitting that one of the strongest reasons it still resonates comes from engineers working quietly behind the scenes. These libraries are not relics. They are living proof that smart, scalable design still has a significant role to play in the future of computing.